Charles Fox

Special to ICT

On the ice, there was freedom for Clarence “Taffy” Abel.

There were few obstacles that the rangy hockey defenseman, known for his “carcass-rattling” style of play, let stand in the way of victory for himself and his teams. An Olympic silver medal and two Stanley Cup championships testify to his success.

When asked what he did for a living, Abel would answer, “I’m in the business of winning.”

But one of his biggest accomplishments still has not officially been recognized amid a tangle of race, ethnicity and identity.

Next year will mark the 100th anniversary of the historic moment on Nov. 16, 1926, when Abel stepped onto the ice for the New York Rangers, becoming the first Indigenous player in the National Hockey League.

No one knew for years, however, that the burly man from Michigan was Ojibwe. And although he has since been inducted into the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame, he still has not been recognized by the NHL for breaking the color barrier in professional hockey.

His nephew, George Jones, 75, who lives in WInter Haven, Florida, believes now is the time, finally, to change that. Jones has fought for years, to no avail, to win recognition for his uncle, who died in 1964 at age 64.

In the year ahead, the New York Rangers will be celebrating the 100th anniversary of the team’s first season, which kicked off on the same day that Abel first took to the ice. And the United States will also be celebrating its 250th birthday next year.

Jones believes now is the best opportunity to get his uncle the honor he deserves.

“He was a trailblazer,” Jones told ICT.

USA Team Captain Clarence “Taffy” Abel leads the U.S. team through the snow-covered streets of Chamonix, France, in the 1924 Olympics, the very first winter Olympiad. Abel, Ojibwe, is still the only Native American chosen to be Olympic flag bearer. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Jones Family Collection

USA Team Captain Clarence “Taffy” Abel leads the U.S. team through the snow-covered streets of Chamonix, France, in the 1924 Olympics, the very first winter Olympiad. Abel, Ojibwe, is still the only Native American chosen to be Olympic flag bearer. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Jones Family Collection

In addition to being the first Native person to play in the NHL, Abel was the first Indigenous American to participate in the Winter Olympic Games. He was a member of the 1924 U.S. Olympics team in men’s ice hockey, and he was chosen as Team USA’s flagbearer for the 1924 Games held in Chamonix, France — the very first Winter Olympics.

“Taffy created a pathway for other people to become accepted,” said Aaron Payment, a tribal board member of the Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians and a distant relative of Abel’s.

“For him to be such a shining example … gives us aspiration to recognize that we can be whatever we choose to be and transcend racism and accomplish whatever we choose,” Payment said. “He’s a big role model for our community.”

The National Hockey League and the New York Rangers did not respond to numerous requests from ICT for comment about Abel. The NHL told The Associated Press in 2022, however, that officials were not comfortable declaring a “first” among Indigenous players because it’s difficult to confirm in some cases.

“Understandably, record-keeping from the earliest days of the league — particularly as it pertained to the race and ethnicity of our players — was not what it is today,” officials told AP.

‘Errors of omission and silence’

The effort to win recognition for Abel has put Jones at odds with the National Hockey League, accusing the league of bypassing his uncle through “errors of omission and silence.”

NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman and other league executives credit Willie O’Ree, the first Black (African-Canadian) player in the NHL, with breaking the league’s color barrier, proclaiming him the “Jackie Robinson of hockey.”

Dr. Sam McKegney, co-director of the Indigenous Hockey Research Network, said O’Ree was “embraced as a signal of benevolence, shifting the racist past into the de-racialized present and future.” McKegney is a professor and head of the department of English literature and creative writing at Queen’s University in Ontario.

O’Ree, from Fredericton, New Brunswick, first played for the Boston Bruins in 1958. His grandparents had escaped slavery in the U.S. through the Underground Railroad. At almost 90, O’Ree remains the Diversity Ambassador of the sport, conducting youth clinics and speaking to groups for almost 30 years. His story pulls at the heart strings, brings anger and tears, and ends in cheers.

“There’s ambassadors, and then there’s Willie,” said former NHL executive Bryant McBride, who was the league’s first African-American executive and oversaw the NHL’s diversity and social justice initiatives from 1992-2000. McBride produced the highly acclaimed documentary, “Willie.”

“He’s going to be 90 this year,” McBride said. “And he still does it. He still has it. He’s incredible. He’s so marketable and you can meet him. And you can press the flesh with him, right?”

Jones believes his uncle has been snubbed, since Abel’s first appearance in the NHL preceded O’Ree’s by 31 years – and nine years before O’Ree was born. The NHL lobbied heavily for O’Ree to be elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2018 and for him to receive the U.S. Congressional Gold Medal, which he received in 2022 from then-President Joe Biden.

Clarence “Taffy” Abel, Ojibwe, was the first Indigenous athlete to play in the National Hockey League. He joined the Chicago Black Hawks in 1929 and played until 1934. This photo is from 1929-1930 hockey season, when he began playing with the team. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Jones Family Collection

Clarence “Taffy” Abel, Ojibwe, was the first Indigenous athlete to play in the National Hockey League. He joined the Chicago Black Hawks in 1929 and played until 1934. This photo is from 1929-1930 hockey season, when he began playing with the team. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Jones Family Collection

Jones believes his uncle was the first Native player in the NHL and that O’Ree was the first Black player. In between there is Larry Kwong, a player of Asian descent, and seven Indigenous Canadians.

Abel, however, spent years keeping his Ojibwe heritage private, “racially passing” as his credentials grew in the field of hockey. It wasn’t until he retired, in 1939, that he finally went public that he was Ojibwe.

As Abel’s legacy fades to become a dusty footnote in history, Jones’ anger has intensified.

“Not to make it about Taffy vs. Willie or Blacks vs. Native Americans, just show some racial justice,” Jones said. “It was tough on all non-White athletes, whatever the sport, in that earlier era. There’s misinformation and disinformation out there, and in my opinion the NHL is responsible for that. Why can’t they just tell the goddamn truth? … It upsets me because they’re letting Native Americans be run over by the bus and to me that’s not fair…I place the blame squarely on the shoulders of [Commissioner] Gary Bettman. Period…Gary did every goddamn thing he could to get his narratives through while erasing the narrative of Taffy Abel.”

Despite his admiration for O’Ree and his own work to build the narrative that surrounds him, McBride feels Abel broke the color barrier.

“I would say yes,” McBride said. “I would define [the barrier-breaker] as anyone who was racially oppressed. … But Taffy wasn’t racially oppressed in terms of his day-to-day, but by virtue of his birth. He was the guy to break the color barrier. So, it’s a two-sided coin again, right?”

The dispute leaves the NHL stuck between competing narratives at a time they are trying to present a more-diverse image.

“The NHL won’t want to diminish Willie,” McBride said. “They’ve gone up there and said he broke the color barrier. Well, Taffy broke the color barrier, but there’s the whole [racial] passing thing. So, it gets sticky for them. … It’s history that is not convenient. It’s not easy. It’s not simple.”

To those who question whether a barrier can be broken in secrecy, Leora Tadgerson, Bay MIlls Anishinaabe and Finnish, director of repatriations and justice at the Episcopal Diocese of Northern Michigan, believes ascribing blame and denying recognition to Abel for racially passing is the “White American lens gaze on the situation.”

“I would want our population to look at a different question at hand,” she said. “Why was a White person fine to play whereas an Ojibwe person was not? What does that say about who we were as a people and how we treated Native populations? …I think we really need to take the pressure off the players themselves and onto the leadership of the organizations.”

‘The Rethink Campaign’

The NHL has made an effort to promote its diversity over the years, unveiling a strategic marketing plan, “The Rethink Campaign, ” in 2010.

Because the league then lacked diversity in both its players and fans, an ad campaign of over $31 million was geared towards Blacks, Latinos, Asians, and other racial and ethnic groups to “rethink” their perception of the NHL in their minds. Television ads featuring O’Ree dominated the campaign during Black History Month and surrounding Jackie Robinson Day on April 15.

Hockey is for Everyone, the community outreach for youth groups and teams, with O’Ree as its “diversity ambassador” since 1998, expanded.

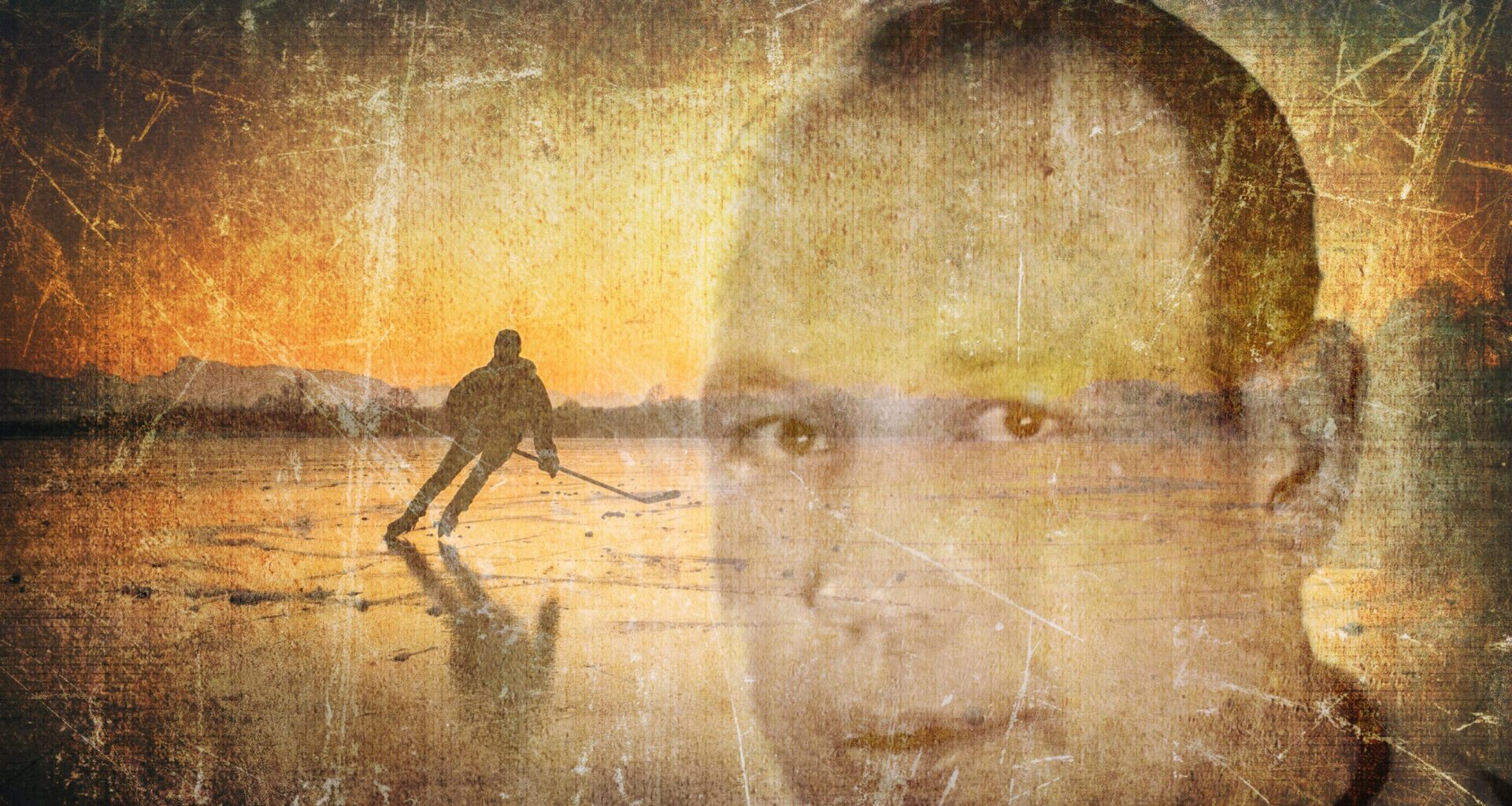

The Taffy Abel Arena on the campus of Lake Superior State University in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan, was renamed for the hockey great in 1993 after renovations. Here, a member of the university team gets in some practice on Sept. 29, 2025. Credit: Charles Fox for ICT

The Taffy Abel Arena on the campus of Lake Superior State University in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan, was renamed for the hockey great in 1993 after renovations. Here, a member of the university team gets in some practice on Sept. 29, 2025. Credit: Charles Fox for ICT

Despite their efforts, an NHL internal study, “Accelerating Diversity & Inclusion,” in 2022 found that 83.6 percent of its workforce and 90 percent of its players, coaches, and officials were White. Only 3.74 percent were Black and 0.5 percent were Indigenous.

In the last two years, however, progress has been made. Approximately 30 Black athletes played during the 2024-2025 NHL season, and in the 2025 draft, more than 20 players of Black, Indigenous, Asian, or Latin American heritage were selected. It was the most diverse draft ever.

Yet while many First Nations players from Canada have played in the league, only eight Native Americans are known to have stepped on the ice in the NHL prior to the 2025 season.

McBride feels that marketing of Native Americans becomes problematic for the populace.

“People won’t talk about Native people,” McBride said. “They just won’t, because it’s too painful. It’s too hard in the face of American exceptionalism to admit that we killed 96 million people. They don’t have the courage and strength to do that.”

While promoting O’Ree and diversity through the years, there has been little recognition by the league of the Native roots of hockey, Oochamkunutk, a game played by the Mi’kmaq First Nation in Nova Scotia, or the now-defunct Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes, a league of over 400 African-Canadians that predated the NHL by 22 years.

“You would think it would actually be an opportunity for the NHL to actively promote the diversity that it’s purporting to be desiring,” McKegney said. “And I think the difficulty is that in doing so, one has to reckon with the actual policies and practices of owners and GMs and coaches and players that were problematic, right? And those aren’t necessarily stories that the NHL wants to tell, even though in doing so it could illuminate the ways that things have evolved positively.”

Eric Hammerstrom, advisor to the Carnegie Initiative and a board member of The Urban Hockey Foundation, offers a more inclusive perspective that creates the case for Abel and O’Ree to both be honored for breaking barriers 32 years apart. As the pendulum swung, each had a different barrier to break, and the times demanded different actions from each.

“We always think of history as being a progressive thing. You make a timeline that goes from left to right. But that it’s not,” Hammerstrom said. “We also have the concept that history is a pendulum swing, that things swing back and forth and back and forth, which suggests that the barrier has to constantly be broken. You don’t break a barrier once and have it go away because, you know, 100 years later, this cycle happens again. And again, somebody has to break a barrier, but in a different way.”

‘Racial passing’

Clarence Abel was born in 1900 in Sault Ste. Marie, also known as “Hockeytown USA,” in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. His nickname, Taffy, would come later in school due to his childhood love of the candy.

He was surrounded by hockey growing up. Sault Ste. Marie and nearby Houghton, Michigan, were hotbeds for early professional hockey leagues shortly after the turn of the century. Abel and friends such as Vic Desjardins, later a teammate on the Chicago Blackhawks, honed their skills on the backyard rink of Sam Kokko on Amanda Street.

Hall of Fame hockey player Clarence “Taffy” Abel, second from left, is shown here at age 15 with friends, from left, Wally Graith, Sam Kokko and Vic Desjardins in 1915. The group played regularly in a rink in the Kokko backyard in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The “N” on the jersey shows they are fans of their hometown “Nationals” hockey team. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Jones Family Collection

Hall of Fame hockey player Clarence “Taffy” Abel, second from left, is shown here at age 15 with friends, from left, Wally Graith, Sam Kokko and Vic Desjardins in 1915. The group played regularly in a rink in the Kokko backyard in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The “N” on the jersey shows they are fans of their hometown “Nationals” hockey team. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Jones Family Collection

Taffy’s father, John Abel, was White, from Fort Wayne, Indiana, and his mother, Charlotte Gurnoe Abel, was from the Chippewa Sault Tribe. Interracial marriages were not uncommon in Sault Ste. Marie for centuries, as European fur traders formed strong ties with Native American communities.

Abel was born into a period when the U.S. government felt the best way to deal with the Native population was to strip Indigenous people of their language, culture and family through boarding schools as a way to force assimilation into White society. It was a period when a knock at the door could mean the arrival of government agents to take the children, creating an atmosphere of constant fear.

The Abel family chose a silent rebellion, refusing to give in to institutional racism to keep their two children and family intact. Taffy and his younger sister Gertrude were light enough in skin color to pass for White. It was known as racial “passing,” a sacrifice made with the hope it would lead to a better life for their children.

“The reason he had to pass was not one of choice — it was one of survival,” Jones said of his uncle. “It was a sad chapter in American history.”

Payment said the tensions brought constant stress.

“If you could pass as not being Native, you didn’t volunteer it,” Payment said. “You didn’t bring any attention to it. And some people today have resentment about that. But then you understand the reason that they did that was to survive, and to get out of the sights of racism.”

Letting their culture take a back seat to the welfare of the children was the cost of keeping their family together. Though they were racially passing, Charlotte and her children were listed as Chippewa (Ojibwe) on the 1908 Durant Roll, the document containing the names of members and descendants enrolled in Michigan tribes.

It would create the tone for the majority of Abel’s life, and he learned at an early age to avoid insurmountable obstacles. He advanced into adulthood hiding his Indigenous identity from public view.

It was knowledge that he carried with him into the hockey rink.

It wasn’t until his mother died in 1939 that Abel broke his silence about his heritage. Following her death, he created the Soo Indians of the Northern Michigan Hockey League in his mother’s memory. It was the first public acknowledgement of their Ojibwe lineage. Abel coached the team, winning three consecutive championships from 1940 to 1942.

“He did it to honor his mother to recognize his Indian ancestry,” Payment said. “That’s a healing step in our community,where you recognize your heritage and then you accept all aspects of yourself.”

Abel had buried his Ojibwe heritage deep inside, a silent warrior. From his first days of school to adulthood, his Native roots and his sense of belonging had been denied, leaving him with a void to fill and decades of depression, his nephew said.

“The effects [of racial passing] are just as culturally devastating as if the cause were forced removal or the boarding school experience,” wrote Bob Antone of Tribal Sovereignty Associates in his paper, “The Power Within People.”

“These beliefs which help us to know who we are and give us purpose, once disrupted, instill a deep sense of loss which is accompanied by the feelings of anger, fear, hurt, loneliness and shame.”

Jones said his uncle struggled with the conflict.

“I know what he had to go through and the internal torment that he had to go through as part of this ‘passing’ thing,” Jones said. “I remember the sadness. That stays with me.”

First Winter Olympics

Dwarfed by Mont Blanc in the background with an elevation of 15,717 feet, USA Team Captain Abel led the U.S. winter team through the snow-covered streets of Chamonix, France, in the 1924 Olympics, the very first winter Olympiad.

The 258 athletes from 16 countries were led by a procession of mountain guides, firetrucks, and the town marching band during the opening ceremonies.

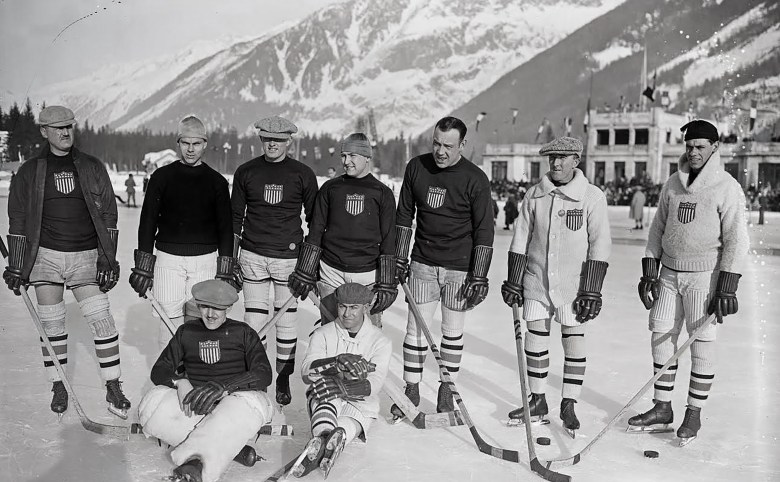

Clarence “Taffy” Abel, third from right, helped lead the USA hockey team to a silver medal at the 1924 Winter Olympics in Chamonix, France. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Jones Family Collection

Clarence “Taffy” Abel, third from right, helped lead the USA hockey team to a silver medal at the 1924 Winter Olympics in Chamonix, France. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Jones Family Collection

Abel proudly clutched the American flag as sunlight beamed through its 48 stars (Alaska and Hawaii were not yet states). Though Abel was considered a U.S. citizen because of his father, Native Americans were not considered citizens until the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 passed later that year in June.

But in addition to carrying the flag, Abel continued to carry the secret of his Native American heritage. Abel recited the Olympic oath on behalf of the American team, “for the honor of our country and the glory of sport.” Yet, the opportunity to honor and bring glory to his Native heritage, for the Native community to partake in the celebration, was missed. It was the only time a Native American has been chosen to be Olympic flag bearer.

Native American athletes had taken part in the 1904, 1908, and 1912 Summer Olympics, with three bringing home medals in 1912: Jim Thorpe, Sac and Fox; Lewis Tewanima, Hopi; and Native Hawaiian swimmer Duke Kahanamoku. Thorpe and Tewanima were both students at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Kahanamoku, a gold and silver medalist in swimming, was not.

When Thorpe was welcomed home from the 1912 Summer Olympics, with gold medal victories in the pentathlon and decathlon, then-President William Howard Taft stated that Thorpe’s victories would “serve as an incentive to all to improve those qualities which characterize the best type of American citizen.”

Ironically, neither Thorpe nor silver medalist Tewanima were considered U.S. citizens at the time.

Their success allowed the federal government to promote Native boarding schools and its assimilation efforts in a positive manner. Because of Thorpe’s success on the football field combined with his gold medal performances in the Olympics, he was generally considered the greatest athlete in the world.

There were no advantages for Abel, however, to declare he was Native, and a declaration could have increased the risk that he might not be put on the roster in a sport that was traditionally segregated.

Prior to the 1924 Olympics, there were other concerns. In 1920, Abel and his friend, Vic Desjardins, who was not Native, had been invited to be part of the Olympic ice hockey team, which oddly was part of the summer Olympics that year.

Since athletes had to cover their own expenses, neither could afford to go. Abel’s father had died that year, making Abel the sole breadwinner for the family. He was an ice sweeper, an “Indigenous Zamboni,” in Jones’ words, and sold programs in exchange for money and ice time.The 1924 Winter Olympics were nearly a fiscal repeat for Abel until friends in Sault Ste. Marie raised money for him to make the trip to Boston for the ice hockey training camp.

By the time Abel was selected for the 1924 Olympics, he had been playing hockey for 14 years on teams such as the Michigan Soo WIldcats, the St. Paul Athletic Club, and the Minneapolis Millers.

He and his U.S. teammates then set sail for Europe. After 10 days at sea on the SS Garfield, including five days in a gale, the U.S. hockey team arrived in the French Alps early hoping for additional practice time only for a snowstorm to dump six feet of snow in a 24-hour period. All available men and the French Army were used to dig out the village and prepare the competition areas.

The extended layoff appeared to not have had a negative impact. Abel scored 15 goals as the U.S. team cruised through its first four matches, outscoring opponents 52-0 on its way to a showdown with Canada.

Both teams were surprised to discover upon arrival that the outdoor rink would be in pond-hockey-style, with no sideboards to bounce the puck or opponents off as they were used to. It didn’t prevent the two teams, playing without helmets and protective gear as was customary at the time, from engaging in what one writer called a testament to “the growing interest in brutal sporting spectacles” leaving the “ice crimson from bloody noses.”

Canada won the gold medal game 6-1, and Team USA took home silver.

Hiding in plain sight

By 1926, Abel had been signed by the New York Rangers along with his Minneapolis Millers teammates, Ching Johnson and Billy Boyd.

Conn Smythe, who was then the Rangers general manager and coach, convinced him to sign the deal in what had turned into a bidding war with the Boston Bruins. Smythe was then fired in the preseason.

The Rangers, a new franchise, took to the ice for their first game of their inaugural season in front of over 13,000 fans on Nov. 16, 1926, in Madison Square Garden, then located on 8th Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets. They were facing the reigning Stanley Cup Champion Montreal Maroons, now defunct.

Except for his large size, there was nothing to draw attention to defenseman Abel. While it was an historic moment for the new franchise, no one, outside of family members and a few friends, recognized it as a historic moment for Abel and Native Americans. As it had been in the Olympics, his historic moment was hiding in plain sight.

“Internally, he could live out his warrior spirit because his new tribe was the hockey team — he actually said that,” Jones said. “It took a lot of balls for my uncle to do that and continue to do that with all the racism going on around him.”

It is unlikely Smythe would have signed Abel had he known about his Native heritage. Twelve years later, in 1938, Smythe, then the owner of the Toronto Maple Leafs, scouted Herb Carnegie, a skilled Black, 19-year-old with the Toronto Junior Rangers now regarded as the best Black (African-Canadian) hockey player never to play in the NHL.

Smythe reportedly told Junior Rangers owner Ed Wildey that “he’d take Carnegie tomorrow if he was White.” More than 50 years later, Carnegie told the story to McBride about being rejected because of his skin color.

“He’s almost 80, cried his eyes out in front of me… And that just seared a hole in my heart,” McBride said.

McBride grew up in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, playing for the Soo Indians, the junior hockey team Abel created in 1939.

“He was amazing, you know, he was an incredible player, well ahead of his time,” McBride said of Abel. “He was huge. You realize how big he was for the time, and he was just monstrous. They said he was 6’2”, 220, but he played closer to 250 pounds. He was just a mountain of a guy for that time. His impact was real. It was very real, and he was a force to be reckoned with.”

The Rangers placed first in the American Division in their initial season. The team, dubbed Tex’s Rangers after their owner, George Lewis “Tex” Rickard, won the Stanley Cup the following year, marking another first for Abel as an Indigenous player.

Hockey great Clarence “Taffy” Abel is shown here in 1929, after his contract was bought out by the last-place Chicago Blackhawks. By 1934, the team had won the Stanley Cup. Abel retired from the team in 1934 after a contract dispute. He played 333 games in the National Hockey League. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Jones Family Collection

Hockey great Clarence “Taffy” Abel is shown here in 1929, after his contract was bought out by the last-place Chicago Blackhawks. By 1934, the team had won the Stanley Cup. Abel retired from the team in 1934 after a contract dispute. He played 333 games in the National Hockey League. Credit: Photo courtesy of the Jones Family Collection

In 1929, the last-place Chicago Black Hawks bought Abel’s contract from the Rangers and by 1934 they had won the Stanley Cup, too. It was Abel’s final season. After a contract dispute with the Blackhawks, Abel retired after 333 games in the NHL, and returned to his hometown. He opened the Log Cabin Café and later Taffy Abel’s Lodge with his wife, Tracy.

He was still considered one of the best defensemen in hockey at the time of his retirement.

“If he would have said at the time, ‘Hey, I’m Native American,’ …They would have said, ‘Well, I don’t think we can do that at this time, come back in 50 years,’” Jones said. “I can tell you, he would have never gotten into the Winter Olympics as a Native American and he never, never, never, would have gotten into the NHL.”

The next Native American player would not enter the NHL until Henry Buccia, an Ojibwe from Minnesota in 1972, 46 years after Abel.

‘Superman with skates’

Abel died of a heart attack in 1964. Six days later, the Sault News ran a story that his Olympic silver medal and the scrapbooks from his career had been stolen. Jones believes the theft occurred during his funeral.

In a 1964 memorial tribute, Herb Levin, sports editor of The Evening News in Sault Ste. Marie, wrote, “In Taffy’s case, it was hard to separate fact from myth.”

The headstone of hockey great Clarence “Taffy” Abel marks his grave at Riverside Cemetery in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, shown here on Sept. 28, 2025 in the Abel family plot. Credit: Charles Fox for ICT

The headstone of hockey great Clarence “Taffy” Abel marks his grave at Riverside Cemetery in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, shown here on Sept. 28, 2025 in the Abel family plot. Credit: Charles Fox for ICT

The man known as the “Michigan Mountain” was often compared to Paul Bunyan, a mythical lumberjack figure. “In the memories of old timers, he was Superman with skates,” Levin wrote.

But Taffy remained Clark Kent, his superhero act done in secrecy, his true identity not revealed until after his playing days had ended. His legacy, however, has endured through generations of hockey players and fans.

Despite the lack of recognition as a Native player, Abel was one of the first inductees into the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame in 1973, and he was inducted into the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame in 1989. Lake Superior State University’s hockey arena in Sault Ste. Marie was renamed the Clarence “Taffy” Abel Arena in his honor in 1993 after renovations. It is the only NCAA hockey arena that has more seats, 4,000, than the university has students. The Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians donated $3 million to the renovation.

Women’s hockey star Abby Roque knows well the Taffy Abel name. Roque, a member of the Wahnapitae First Nation, a band of the Ojibwe tribe, represented the U.S. at the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, becoming the first Native American woman on the women’s hockey team.

“I’ve known the name my whole life,” Roque said. “The Taffy Abel Arena was basically the place I learned how to play hockey and the place I skated almost every day…Honestly, I was a little rink rat.”

Roque now plays for the Montreal Victoire of the Professional Women’s Hockey League.

“We both came from Sault Ste. Marie,” she said. “He got to be the first Indigenous hockey player for the USA and me being the first one on the women’s hockey team. It’s very special, Sault Ste. Marie having two players who’ve made it to the highest point in our careers making it to the Olympics and playing professionally.”

Her father, Jim Roque, who coached hockey at Lake Superior State University and is currently a scout for the Toronto Maple Leafs, had also racially passed growing up due to his mother’s fear of the Canadian Indigenous residential schools 60 years after the Abel family had done the same. Jim Roque said the silence of the league and the Rangers is disappointing to him.

“Native Americans have been great athletes for a long time,” Jim Roque said. “And they seemed to have sprinkled themselves in different sports a lot earlier than other people of color, which maybe normalizes it a little bit. Do I think they should get recognized more? No doubt.”

He said he believes the Native American athletes who’ve broken barriers have not been recognized as well as other athletes.

“It seems a different standard,” he said. “Taffy Abel is an Olympian who played in the NHL. I don’t know what more you want from a guy, right?”

Related by love

In 1967, George Jones, then 17, made the drive from his hometown of Peoria, Illinois, in his 1960 Ford Falcon to Sault Saine Marie to honor the uncle who, not having his own children, “treated him like the son.” It was a pilgrimage of gratitude to Riverside Cemetery after being unable to attend the funeral three years earlier.

Related by the marriage of his Aunt Tracy, his mother’s sister, to Abel, Jones is fond of saying that he and Abel “are related not by blood, but by love.”

The words he spoke at the gravesite remain private, but his efforts to honor his uncle have been outspoken, often critical of the NHL. Jones has created a website featuring volumes of information, links to articles, and historic photos of his uncle. It serves as his podium and his courtroom as he presents his case against the NHL.

Hoping for a league acknowledgement of the centennial of Abel’s appearance in the 1924 Winter Olympics, he mailed over 50 glossy cards listing Abel’s accomplishments to NHL executives, governors, and team owners in 2022. Only Dick Patrick, president and part-owner of the Washington Capitals, responded and offered to reach out to league executives. Patrick’s grandfather, Lester, was Abel’s first NHL coach, and Abel was one of the pallbearers at Lester’s funeral. Yet nothing materialized from the conversation, Jones said.

As the centennial gets closer, Jones’ phone calls, emails, and meeting invitations to NHL executives and owners go unanswered.

“Say the name Taffy Abel, and they’re like, oh God, what does he [Jones] want?” says McBride, the former NHL executive. “They have guard up on this one.”

Jones has reached out in recent weeks to the NHL Alumni Players Association and USA Hockey, but only the New York Rangers Fan Club has agreed to identify Abel as the breaker of the NHL color barrier.

“I have hit this pretty damn hard, and I’m always wondering when I wake up in the morning or go to bed at night, what could I do better?” he asks.

Jones refuses to give up.

“Like Taffy,” he says, “I’m in the business of winning.”

Related