The Athletic has live coverage of opening night of the 2025-26 NHL season.

In July, nearly four decades after they were college teammates, Mike Sullivan and Joe Sacco sat together in the Popponesset Inn, each nursing a beer. They were visiting Cape Cod and had golfed that day in an annual charity tournament attended by fellow Boston University alumni.

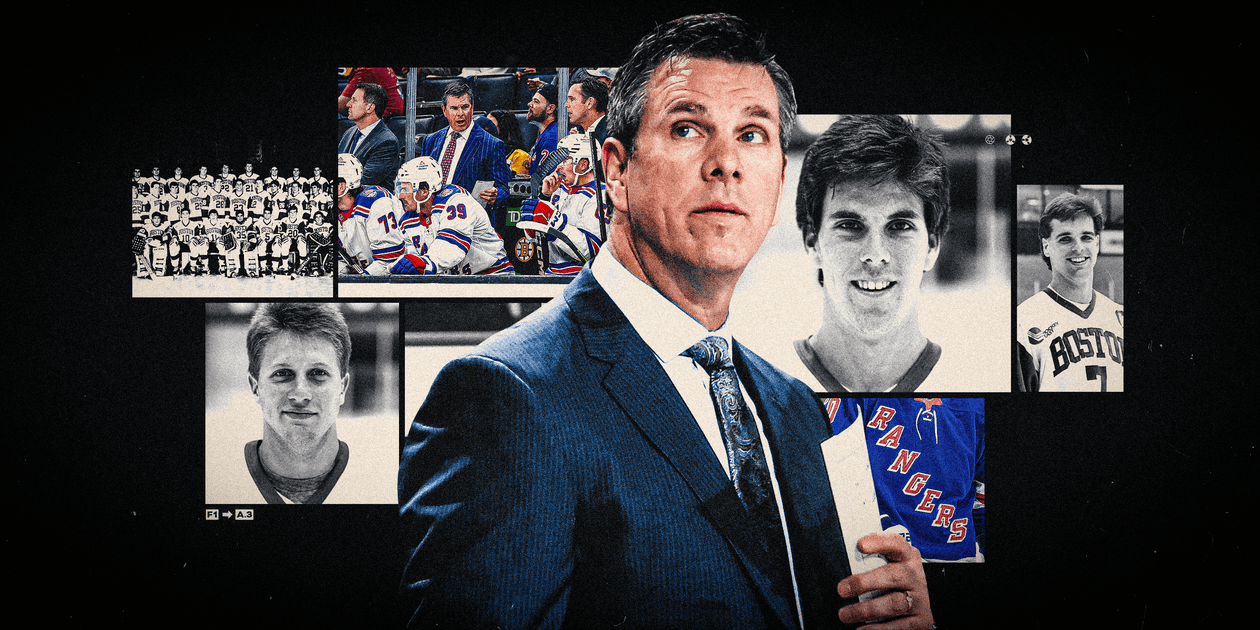

Jack Parker, their former coach with the Terriers, spotted his old players as he walked into the inn for the evening cocktail hour. They began catching up, and Parker quickly pointed out that Sullivan, hired by the New York Rangers as head coach in May, had brought along Sacco and David Quinn, another former BU teammate, as assistants.

“None of you guys ever think of cutting me in on anything,” quipped Parker, who is heading into the Hockey Hall of Fame in November. “Where’s my 10 percent?”

That earned a round of laughs, but there’s truth to the sentiment. As Sullivan says, Parker is “the common denominator through all of us.” With the legendary coach at its helm, BU served as a springboard for Sullivan, Quinn and Sacco to each have decades-long hockey careers as players and coaches. Ditto for the trio’s new boss, Rangers president and general manager Chris Drury, who played under Parker at BU too, though after the three coaches.

Sullivan, who could someday join Parker in the Hall of Fame, will make his Rangers head coaching debut Tuesday against the Pittsburgh Penguins, his former team. Coming off a 10-season stint in Pittsburgh during which he won two Stanley Cups and established himself as one of the most respected coaches in the league, Sullivan and the club mutually agreed to part ways in April after three straight years of missing the playoffs. That allowed Drury, who had long coveted the coach, to pounce.

Less than a week after Sullivan’s departure, the Rangers gave him a five-year deal worth $6.5 million annually, the highest coaching salary in the league at the time of his signing.

The Rangers are trusting Sullivan to not only bring top-notch hockey knowledge but also stabilize an organization that went through a tumultuous 2024-25 season. In turn, the coach is trusting his two college teammates and longtime friends to help make that happen. For the first time since 1987-88, the lone season the trio spent together at BU, they’ll once again share the same bench.

“The fact that we have established friendships off the ice, for me, is a bonus,” Sullivan says. “But that by no means was the impetus why these guys have joined the staff.”

That reason is, in large part, experience. All three have been NHL head coaches: Sullivan with Boston (2003-06), Pittsburgh (2015-25) and now New York; Quinn with New York (2018-21) and San Jose (2022-24); and Sacco with Colorado (2009-13) and as an interim in Boston (2024-25). All have multiple experience as NHL assistants, too.

Not bad for one college roster.

Upon enrolling at BU in 1986, Sullivan moved into a freshman dorm room around 300 square feet in size. Matt Pesklewis, his roommate and hockey teammate, had arrived before him and already put up a Pink Floyd poster. Not knowing that Pink Floyd is a rock band, Sullivan was initially worried he’d been paired with a heavy metal fan.

“We ended up sharing each others’ musical stuff, just embracing the differences,” says Pesklewis, who was moving to Boston from Alberta. “I think Sully was really good at that. He understood that I came from a different place. … Pink Floyd wasn’t heavy metal, and I think it’s one of his favorite groups now.”

When the holidays rolled around, Sullivan invited Pesklewis over to his family’s home in Marshfield, Mass., southeast of Boston. That meant a lot to a homesick kid across the continent from his family. Pesklewis quickly saw Sullivan as a leader — someone he could emulate.

Sullivan instantly noticed Quinn at the Terriers’ first off-ice workout of the year. He “had a physical stature like a Coke machine with a head on it,” Sullivan remembers. The defenseman, who was two years ahead of Sullivan, was a first-round pick of the Minnesota North Stars in 1984 and one of the team’s most promising NHL prospects. When they got on the ice, Sullivan was blown away by Quinn’s skating. He was as fast going backward, Sullivan thought, as much of the team was moving forward.

Sullivan and Quinn became fast friends, and Quinn went on to serve as a groomsman when Sullivan married his wife, Kate. Parker says they quickly showed the personality of leaders while at BU. Teammate Mike Kelfer believes both mirrored their legendary coach’s diligence.

The Terriers’ team was tight-knit; Sullivan viewed it as an instant friend group when he got to BU. They ate pregame meals together at T. Anthony’s by campus, and spent countless hours at the rink. Away from it, Sullivan says they did “what every other college person did” for fun. Goalie Peter Fish laughs as he recalls Quinn and Sullivan watching him play Super Mario on his dorm-room Nintendo Entertainment System.

“(They were) always making fun of me because I could never get the princess,” says Fish, now an NHL player agent.

Sullivan had braces when he got to campus, longtime BU announcer Bernie Corbett remembers, and proved an immediate contributor. He scored 13 goals and totaled 31 points over 37 games in 1986-87, with BU winning the Beanpot in an 4-3 overtime thriller over Northeastern.

In another game, a month earlier at home against Minnesota, Quinn sprung Sullivan on a breakaway with a stretch pass. The forward deked past the goaltender, backhanded the puck into the net and then slid into the boards. As he got up, Quinn patted him on the helmet in celebration.

After a recent Rangers’ preseason game, Sullivan was shown a video clip of the goal.

“Way back in the day,” he said. “Pretty good!”

Then-forward Mike Sullivan skates for the BU Terriers. (Courtesy of BU Athletics)

When Parker first sat in Sullivan’s living room on a recruiting trip, he was immediately struck by the young forward’s maturity: a sense of self not always present in recruits that age. As a player, Parker liked Sullivan’s size and hands, but felt he labored too much while skating. If he had that ability, the coach thought, he’d be a terrific player.

At BU, Sullivan did everything in his power to improve his skating. Working tirelessly with strength and conditioning coach Mike Boyle, he grew faster every year, Parker said. By the time Sullivan reached the NHL, he could fly: In the fastest skater competition at the 1993 All-Star Game, he finished second only to New York’s Mike Gartner.

Sacco, meanwhile, was a strong skater from the start. He came to BU in 1987-88, a year after Sullivan and Quinn’s senior season. He was an immediate contributor, averaging more than a point per game. He was a hard, tenacious player: “a pain in the a– to play against,” Pesklewis says.

Sullivan and Sacco were both wingers, and both had Parker’s trust.

“They weren’t necessarily Jack Eichel or Connor McDavid, but they were the type of players that every team needed,” Fish says. “Your heart and soul.”

Quinn was a co-captain Sacco’s freshman year — the trio’s lone college season all together — but he was medically unable to play. After his junior season, he was diagnosed with Christmas Disease, a rare form of hemophilia that all but ended his playing career. Though he wasn’t with the team on the ice, Sullivan remembers him being around “all the time” away from it. Memories from that time are hazy, but some around the team at the time think he might’ve even been on the bench with the coaches for a few games.

“He was one of us,” Sullivan says of Quinn. “Even though he wasn’t playing he was every bit a captain as part of that team.”

Quinn even stayed on campus for a fifth year and, at the request of Parker and assistant Ben Smith, coached the Terriers’ junior varsity team. He also worked with Corbett as a color analyst for some high school hockey broadcasts. On at least one occasion, Corbett says, they called a Keith Tkachuk game while he was at Malden Catholic.

In Parker’s memory, Quinn was the most outgoing of the three future Rangers coaches and Sacco the quietest. The latter once scored five goals in a Hockey East playoff game, but Parker says you wouldn’t have been able to tell he’d scored one.

Sullivan was between his future assistants on that spectrum, Parker continues. His teammates voted him captain in 1989-90, his senior year. Tomlinson, who went on to spend parts of four seasons in the NHL, describes Sullivan as a team-first, selfless player.

“I put him right up there as one of the best captains with which I played,” Tomlinson says.

“One of Jack’s all-time favorite captains,” Corbett adds of Parker.

One night, in November 1988, BU blew out Providence on the road. Playing on a line with Sacco, both Tomlinson and Kelfer registered seven points, tying a Hockey East single-game record.

Late in the game, Tomlinson had the puck on a power play and faced a choice between shooting or passing to Sullivan. Knowing he was having a historically magical game, Tomlinson chose to shoot. It didn’t work — and worse, it was the wrong hockey play. During a stoppage, when Sullivan told him to move the puck, Tomlinson chirped back that he was going for the record.

That wasn’t good logic in the eyes of the future coach.

“He just chewed me out and put me in my place pretty quickly,” Tomlinson remembers.

The message was clear and received: The team, not individual achievement, came first.

Sullivan, left, and Quinn coached together last season with the Penguins. But 2025-26 marks the first time they’ll share a bench with Sacco too. (Matthew Huang / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images)

At the end of Sullivan’s senior year, the Terriers played top-seeded Michigan State for a chance to advance to the Frozen Four. Teams played best-of-three series in the NCAA tournament back then, and Sullivan was nursing a bad ankle that sidelined him for the first game, a BU loss. Ahead of Game 2, with his college career on the brink and the Terriers down another key forward in Tomlinson due to a Game 1 penalty, Sullivan approached Parker.

“I’ll fill in,” the captain told the coach then.

“He could barely drag his right leg around,” Parker says now.

And yet he played, even scoring a goal. The next night, in a decisive Game 3, Sullivan and Sacco both had assists to help BU complete an upset and reach its first Frozen Four since 1978.

After a Frozen Four loss to Colgate — Sullivan still laments one of his teammates’ shots hitting the post in a 3-2 defeat — both Sullivan and Sacco turned pro. Sacco went on to play 738 NHL games with the Maple Leafs, Ducks, Islanders, Capitals and Flyers. Sullivan, a fourth-round pick by the Rangers, carved out a 709-game career for the Sharks, Flames, Bruins and Coyotes.

New medications allowed Quinn to make a comeback bid in the early 1990s, but he had been away too long to play more than two minor league seasons. He entered coaching as an assistant at Northeastern and started moving up the career ladder. Two decades later, in 2013, he succeeded Parker as Boston University’s head coach.

Sullivan and Sacco joined Quinn in the coaching ranks in the early 2000s, after their playing days were done. In Sullivan’s opinion, Parker strongly influenced how all of them think about hockey and teach it to their players: one of Parker’s greatest strengths.

Parker says he never thought about any of his players someday becoming coaches: “I wouldn’t wish that on anybody!” he jokes. But plenty of Sullivan’s former teammates aren’t surprised at where he’s ended up. Clark Donatelli, who played with Sullivan at BU and later worked under him as an AHL coach in the Penguins’ organization, “just knew he’d always be a coach” because of how smart a player he was. Kelfer speculated with teammates during their college days that he “might be one guy to replace Coach Parker.”

Before reuniting in New York, the trio’s respective coaching journeys overlapped a little — but not a ton. Sullivan and Sacco had never worked together before this season. Quinn had one prior season as an assistant for each of his former teammates: with Sacco in Colorado in 2012-13 and with Sullivan last year in Pittsburgh. He’s also been on Sullivan’s staff for two international tournaments, the 2007 world championships and February’s 4 Nations Face-Off. Sullivan will also serve as the United States’ head coach at the 2026 Winter Olympics, and he’s bringing Quinn along on his staff.

Even though Sullivan hasn’t seen Quinn and Sacco coach up close like he can now, he’s long appreciated their work. Sacco spent more than a decade as an assistant on Bruins teams that regularly made the playoffs and reached Game 7 of the Stanley Cup Final in 2019. Quinn helped the Penguins’ power play rise from 30th in the league in 2023-24 to sixth last season. The head coach said he was instantly interested in bringing his former teammates to New York when he got the job.

“To have the opportunity to coach the Rangers with these guys just makes it that much more special,” Sullivan says. “We’re going to go through ups and downs over the course of the year, but I couldn’t be happier to go through ups and downs with guys like Joe and Quinny.”

The assistants’ experience only helps as much as they’re comfortable sharing it, but there’s no holdup there on the Rangers’ staff. Quinn runs the Rangers’ power play and works primarily with the defensemen, while Sacco is tasked with the forwards and penalty kill. During scrimmage work at Monday’s practice, Sacco and Quinn stood on opposite benches, and Sullivan rotated between both of them. When the team did drills, the three were in lockstep when directing players where to go.

“One of the nice things about having an established relationship the way we do is there’s really not a feeling-out process,” Sullivan says. “Everybody speaks their mind pretty freely.”

Sullivan notices himself laughing a lot since he began sharing a coaches’ room with Quinn and Sacco. Sometimes they crack up talking about Parker: how he intimidated them all back in their playing days and never shied from barking at his teams.

Now 80, their former coach loves that they’ve all ended up together with the Rangers.

“It looks,” Parker says, “like BU Southwest.”