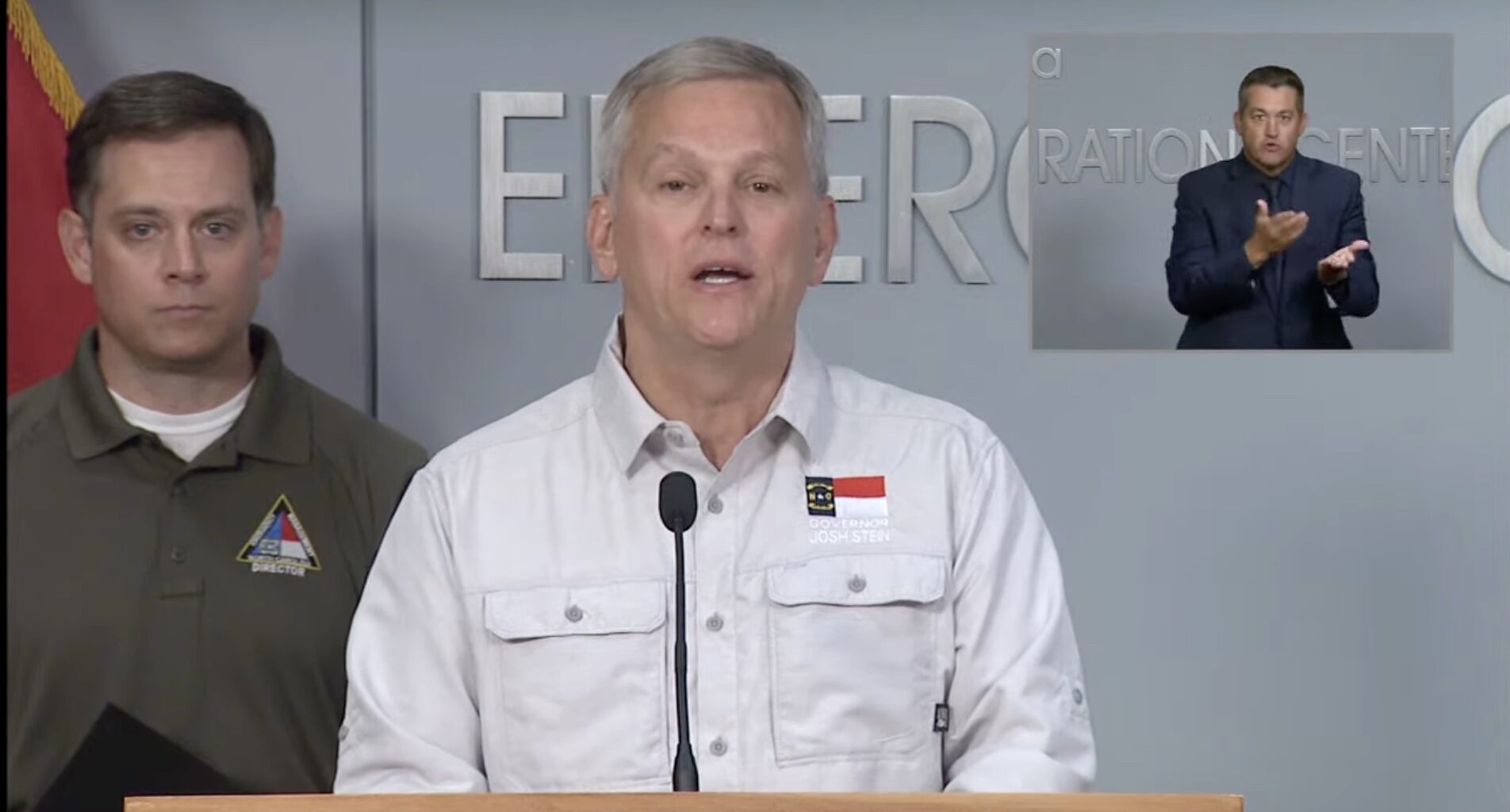

Gov. Josh Stein recently tried to convene an emergency session of the General Assembly. Fortunately, legislative leaders pushed back. First, the General Assembly is already in session; and second, no extraordinary circumstance exists to justify the governor’s use of the power to call a legislative session.

When North Carolina’s framers wrote that the governor could convene the General Assembly on “extraordinary occasions,” they knew exactly what they meant. They meant hurricanes. Floods. Disasters that kill people and destroy communities overnight. They did not mean budget disputes.

Article III, Section 5(7) of the North Carolina Constitution gives the governor power to call emergency sessions, but only “on extraordinary occasions” and only “by and with the advice of the Council of State.” Both requirements matter. The framers made emergency sessions hard to call because they understood the temptation to manufacture crises for political gain.

North Carolina’s history provides stark examples of genuinely extraordinary occasions. Hurricane Hazel in 1954 hit with 150 mph winds, killed 19 people, and destroyed over 15,000 buildings. Hurricane Floyd in 1999 killed 52 North Carolinians and caused $6 billion in damage when catastrophic flooding submerged entire eastern counties. Hurricane Florence in 2018 killed 53 and caused $16.7 billion in damage. Hurricane Helene in 2024 killed at least 107 people, with western North Carolina still rebuilding more than a year later.

When hurricane winds bulldoze our communities, normal governmental processes are inadequate. This is what “extraordinary” means.

North Carolina’s 1776 constitution established a legislature-dominated government precisely because colonists had suffered under royal governors who abused their executive authority. The early governor couldn’t convene the Assembly, had no veto power, and served only one year at the legislature’s pleasure.

The 1835 reforms introduced popular election of governors. The 1868 constitution established four-year terms. A 1996 amendment gave the governor a limited veto power. Throughout these changes, the emergency session power remained tethered to genuine crises and required consent from the Council of State, independently elected officials representing diverse constituencies statewide.

This Council of State requirement is critical. It prevents governors from manufacturing emergencies for political advantage. Before calling an emergency session, a governor must convince other elected officials that circumstances truly warrant disrupting the legislative calendar. This safeguard distinguishes North Carolina from states where governors can unilaterally call special sessions for any reason.

North Carolina statute G.S. 166A-19.20 explicitly recognizes what constitutes an extraordinary occasion: when the Transportation Emergency Reserve is exhausted during actual disaster response. The statute links emergency sessions to depleted emergency funds during real disasters — not to political disagreements about budget priorities.

This reflects proper understanding. Emergency sessions are for when critical infrastructure or public safety funding runs out while responding to hurricanes, floods, or similar catastrophes. They’re not for when political majorities disagree about Medicaid funding or education policy.

Budget disputes are ordinary legislative business. They should be resolved through regular sessions and normal democratic processes. Even significant funding challenges in government programs don’t meet the constitutional threshold. These issues are important, but they’re not emergencies.

Perhaps most telling about the manufactured nature of this crisis is a simple fact: the North Carolina General Assembly is currently in session. The constitutional power to convene an “emergency” session exists precisely for situations when the legislature is not in session and cannot respond to urgent crises. But when the General Assembly is already convened, there is no need to “call” them into session. They’re already there. The very act of invoking emergency session powers under these circumstances reveals this for what it is: political theater masquerading as constitutional crisis.

Each time a governor calls an emergency session for what amounts to routine political business, the constitutional standard weakens. Future governors find it easier to justify emergency sessions for increasingly ordinary matters. The Council of State’s checking function erodes as emergency declarations become normalized.

North Carolinians who survived Hazel, Floyd, Florence, and Helene understand viscerally what “extraordinary occasions” means. It means homes underwater, communities destroyed, neighbors dying, and state government mobilizing with appropriate urgency to address unprecedented disaster.

It does not mean political maneuvering in budget negotiations, however important those disagreements may be.

The emergency session power represents constitutional wisdom: creating governmental flexibility for genuine crises while building in safeguards against abuse. When the next Category 4 hurricane inevitably strikes North Carolina, the governor must be able to act immediately to convene the legislature.

But this power retains legitimacy only if reserved for true emergencies. Converting routine governance disputes into constitutional emergencies dishonors both the framers’ intent and the real needs of North Carolinians who depend on emergency powers being available — and credible — when disaster strikes. The people whose homes were destroyed by Hurricane Helene, whose communities were submerged by Hurricane Floyd, whose lives were upended by Hurricane Florence — they represent the constituency the framers sought to protect.

Emergency sessions were built for them. For hurricanes and floods and disasters that kill. Not for politics.