With the 2026 Winter Olympics just days away and four Winnipeg Jets set to compete, a remarkable moment in Canada’s hockey history is about to be brought back into the spotlight.

On February 4, the Winnipeg Jets will honour the 1920 Winnipeg Falcons with a special video tribute at Canada Life Centre during their Olympic send-off game against the Montreal Canadiens. The Falcons were the first team ever to win Olympic gold in hockey for Canada, yet many modern fans don’t know their story.

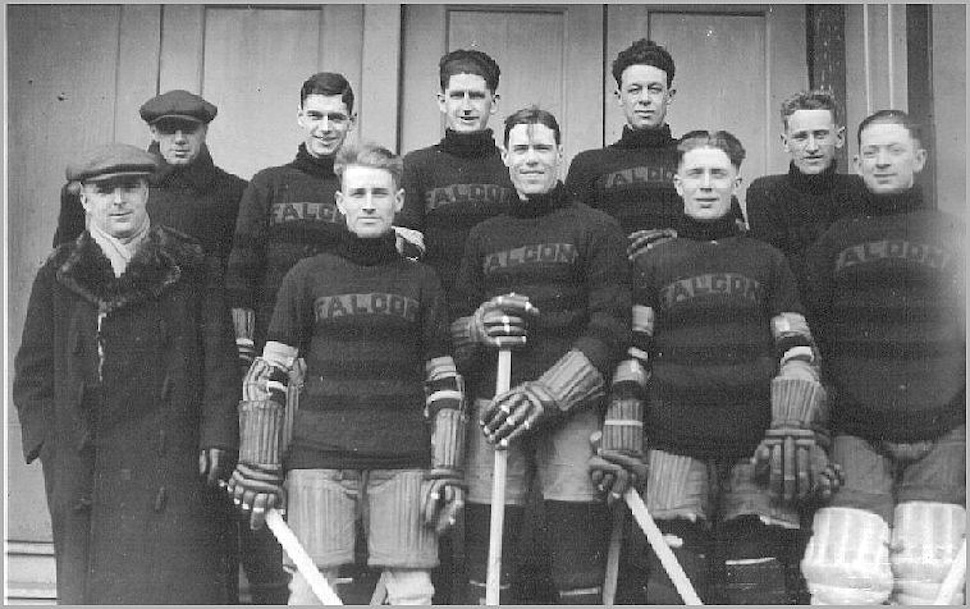

What makes the Falcons even more extraordinary is that nearly every player on that team was a first- or second-generation Icelander from Winnipeg’s West End. It’s a legacy championed by local enthusiast Rod Palson, who has worked to bring renewed attention to the team’s history.

Listen to the full interview with Palson here

Icelandic roots and early discrimination

Rod Palson says his own Icelandic heritage fuels his passion for preserving the Falcons’ legacy. He says that although he has always considered himself a proud Canadian, he is even prouder of his Icelandic roots. (Mike Thom/PNN)

Rod Palson says his own Icelandic heritage fuels his passion for preserving the Falcons’ legacy. He says that although he has always considered himself a proud Canadian, he is even prouder of his Icelandic roots. (Mike Thom/PNN)

About 14 months ago, Palson began thinking about the upcoming Olympic year and the approaching milestone marking 150 years since the first Icelanders arrived in Manitoba, and saw an opportunity to renew interest in the Falcons.

Palson said many hockey fans he knows have heard of the Winnipeg Falcons but did not realise the team won Canada’s first Olympic hockey gold medal or that its players were largely of Icelandic descent. He said that legacy is a deep source of pride within the Icelandic community and deserves wider recognition.

The Falcons’ story began in the late 19th century when Icelandic immigrants settled in Manitoba, learning a new language and adapting to a new way of life. Over time, they also learned the game of hockey.

Early Icelandic players formed teams such as the Icelandic Athletic Club and the Vikings, competing mostly against each other because of discrimination.

Those teams eventually combined to form the Winnipeg Falcons. Despite their growing skill, Palson explained that established teams in Winnipeg initially refused to allow the Falcons into top-tier leagues, underestimating them and discriminating against them because of their background and language. That changed only after the Falcons became too good to ignore.

From underdogs to Olympic gold medallists

Once admitted to higher competition, the Falcons quickly proved themselves. They won the Western Canadian Championship and then captured the Allan Cup, earning the right to represent Canada at the 1920 Olympic Games in Antwerp.

Hockey and figure skating were official medal sports at those Summer Games, and the Falcons dominated the tournament. They defeated Czechoslovakia 15–0, shut out the United States 2–0, and beat Sweden 12–1 to secure the gold medal, marking the first Olympic hockey championship in history.

Many members of the Falcons had recently returned from serving in the First World War, and two players never came home. Palson said the surviving players regrouped after the war, added new teammates and rebuilt the team that would go on to Olympic glory.

He shared stories about star player Frank Fredrickson, a prolific goal scorer who survived a wartime torpedo attack, rescued his violin from a sinking ship and later became one of the first players to win both a Stanley Cup and an Olympic gold medal.

Fredrickson eventually coached hockey at Princeton University and formed a friendship with Albert Einstein, another accomplished violinist.

Palson also says that the Falcons sailed to Europe without proper equipment. Their hockey sticks were carved from a block of wood by a ship’s carpenter in Montreal, and after winning gold, the Falcons gifted those sticks to the Swedish team as a gesture of sportsmanship.

Jets tribute aims to revive a fading legacy

When the Falcons returned to Canada in 1920, they were celebrated widely. They received a hero’s welcome in Toronto and were greeted in Winnipeg with a parade down Portage Avenue.

Despite that celebration, Palson said the Falcons’ story faded over generations, even within Icelandic families. He said that gradual loss of awareness is one of the main reasons he wanted to help bring the story back into the public eye.

That effort will be on full display on February 4. During the Jets’ game against the Montreal Canadiens, a professionally produced tribute video will be shown on the big screen at Canada Life Centre. Descendants of at least three Falcons players are expected to attend, representing third- and fourth-generation families who continue to take pride in their connection to the team.

Palson is encouraging fans, particularly those with Icelandic roots, to show their pride by bringing flags or signs and cheering loudly when the tribute plays. He also hopes all fans will join in, regardless of heritage, and celebrate the Falcons’ place in hockey history.

Palson said the event is about more than one night at a Jets game. He hopes it helps extend the story of the Winnipeg Falcons to a much broader audience and ensures that Canada’s first Olympic hockey champions are no longer forgotten.

Roster of the Olympic champion Winnipeg Falcons:

Information provided by the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame.

Players:

Frank Frederickson (Captain), Allan “Huck” Woodman, Haldor “Slim” Halldorsson, Kurt ‘Konnie’ Johannesson, Christian Fridfinnson, Bobby Benson, Magnus “Mike” Goodman, Wally Byron.

Falcons that were not on the Olympic roster but contributed during the season were Harvey Benson, Ed Stephenson, Connie Neil, W. B. ‘Babe’ Elliott, Babs Dunlop and Sam Laxdal.

Staff:

Fred “Steamer” Maxwell (Manager & Coach), W.A. Hewitt, Olympic Team Manager, Gordon Sigurjonsson, Trainer.

Honorary President, Hon. Thomas H. Johnson; President, Hebbie Axford; Vice-President, Col. H. Marino Hannesson; Secretary, Bill Fridfinnson; and the executive committee consisted of Bob Forrest, John Davidson and Fred Thordarson.