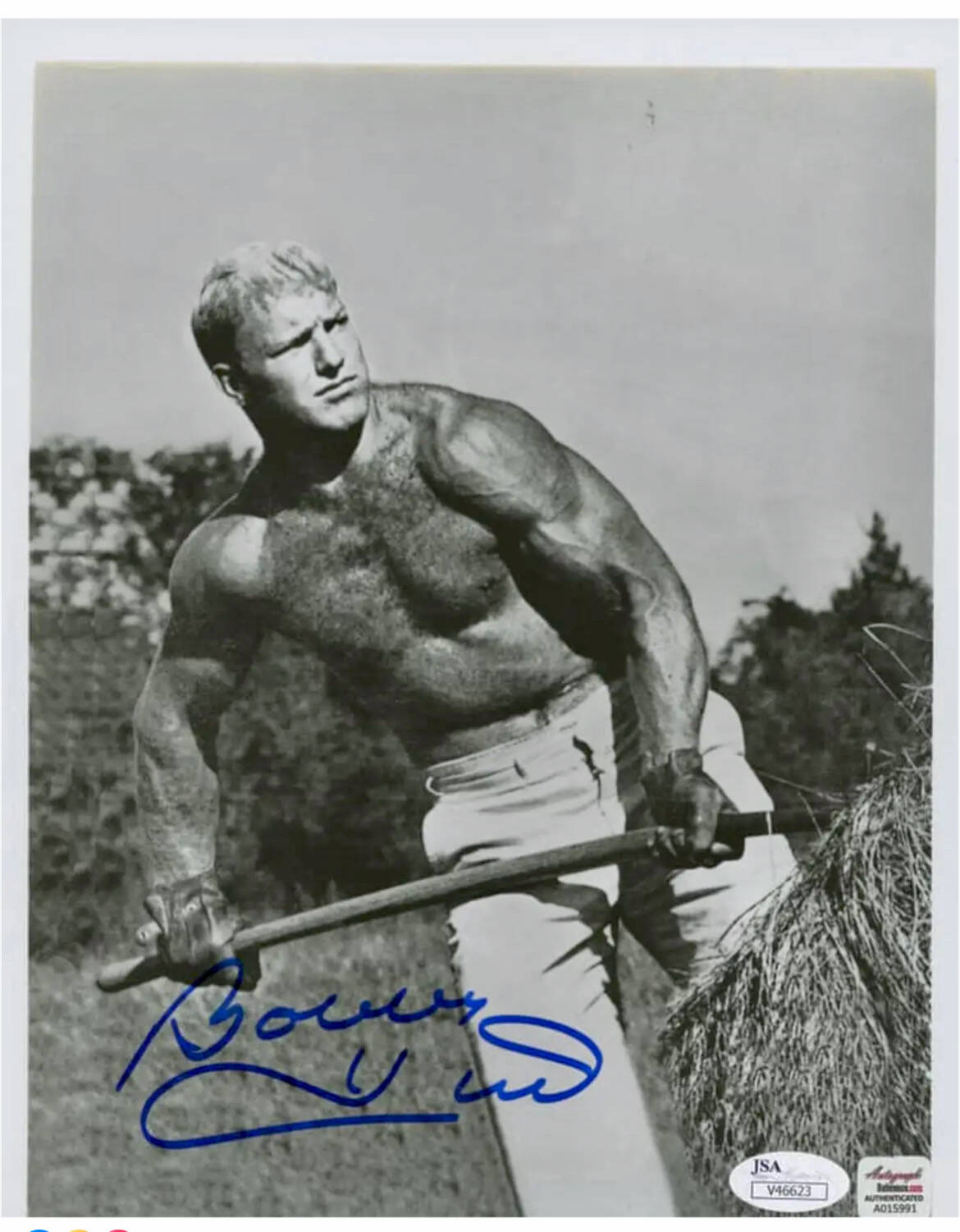

WINNIPEG — There’s an iconic photo from the 1960s that captures the connection between hockey and farming in Canada.

In the black and white picture, a shirtless and muscular Bobby Hull is pitching hay on his farm in Ontario.

The photo embodies the Canadian story about back-breaking farm labour and how that prepares young men for a career in the National Hockey League.

Read Also

TEAM readers have fond memories, recipes in particular

We recently asked our readers for their thoughts and memories of 30 years of TEAM Resources columns published in the Western Producer. Here are some of their responses.

“It was working on the family farm and throwing bales of hay that set my arm up for the slapshots I was later known for,” Hull told the Belleville Intelligencer in 2001.

Bobby Hull, who was famous for his curved stick and slapshot, developed his strength by working on his Ontario farm. Photo: Screencap via facebook.com

Bobby Hull, who was famous for his curved stick and slapshot, developed his strength by working on his Ontario farm. Photo: Screencap via facebook.com

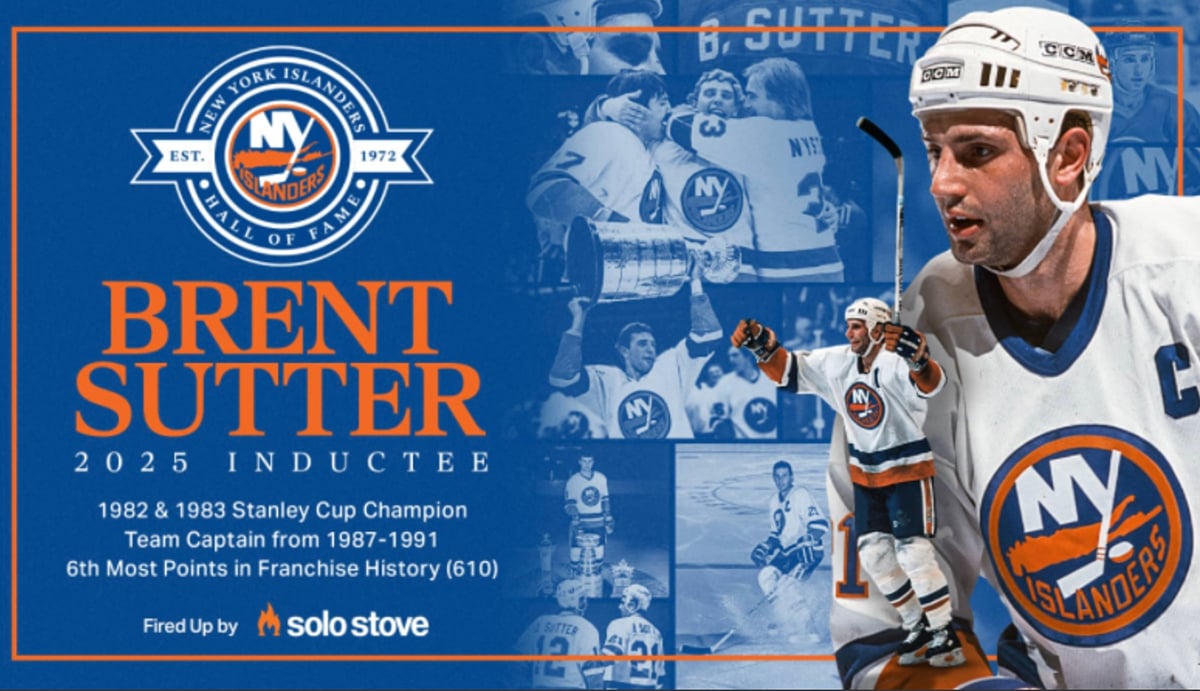

There are similar legends about hockey and farming in Western Canada, with the most famous being the six Sutter brothers of Viking, Alta. — Brent, Brian, Darryl, Duane, Rich and Ron.

The Sutter boys were raised on the family farm and all six thrived in the Western Hockey League and the NHL in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

Brent Sutter, who played for the Islanders and Blackhawks and owns the Red Deer Rebels of the WHL, has a clear memory of working on the farm in his teens.

He fed pigs, took care of the chickens and milked cows.

He also did field work, putting in time on the tractors.

“You had things to do and you had to get it done,” said Sutter, who is 63.

“Mom and Dad held us accountable to make sure it got done…. That was the bottom line.”

In an interview with the Western Producer, Sutter said there’s a direct relationship between his childhood and his success in professional hockey.

It gave him the “discipline, work ethic (and) accountability” that’s needed in the NHL.

Sutter’s experience in Viking probably sounds familiar to tens of thousands of kids who grew up on farms in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

Everyone was expected to help and do their bit, even hockey players selected in the first round of the NHL draft.

But does that connection between “hard work” on a farm and success in hockey still ring true in 2026?

Is it possible for a farm kid from Wadena, Sask., to make the NHL?

Absolutely it is.

However, that teenage hockey player may follow a very different path than players in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

He’ll probably spend much more time on the ice and very little time on a tractor.

No time for farm work

Ken Schneider grew up on a grain farm in Colfax, Sask., north of Weyburn. He played for local hockey teams in southeastern Saskatchewan in the 1970s, then the Brandon Wheat Kings for two years and was captain of the Wheaties in the 1981-82 season.

Four decades later, Schneider is still involved in the sport. He’s an assistant coach with the Regina Pats in the WHL.

Like Sutter, Schneider can easily remember the work he did on the family farm 50 years ago and how it shaped his life.

One of his jobs was getting grain bins ready for seed storage.

“My younger brother and I would spend a day cleaning bins. Then (my dad) would come along and bang the walls with his broom and we would be frustrated as hell,” he said.

“Stuff would fall and he’d say, ‘get back in there, it’s not done.’ ”

Schneider didn’t enjoy cleaning grain bins as a teenager, but he did learn important lessons about taking direction and doing things the right way.

These days, teenage hockey players have little time for on-farm labour and the related life lessons because they’re always on the ice.

Many of them live away from home 11 months of the year.

“We have kids (on the Rebels) that come from farms … but it’s different now because kids can leave (home) during the winter,” said Sutter, who won two Stanley Cups with the New York Islanders.

“You can be from Manitoba and come play in Alberta at an academy.”

In the last 20 years, dozens of hockey academies have popped up across Western Canada, where boys and girls go to school and play hockey six or seven days of the week.

Some elite players will leave home at age 13 or 14 to attend an academy, hundreds of kilometres from where they live. When the school year ends, many will train at a hockey skills program for a month in the summer, or maybe all summer.

That’s completely different from the teenage life of Warren McCutcheon, who now runs a grain farm in Carman, Man.

He spent much of the 2000s playing in the WHL, for the University of Manitoba Bisons and in the minor leagues.

Warren McCutcheon, who played hockey in the 2000s and now runs a grain farm near Carman, Man., says staying on the farm during his playing years had its benefits, but the concept of taking a summer break from the game has since faded away. Photo: Supplied

Warren McCutcheon, who played hockey in the 2000s and now runs a grain farm near Carman, Man., says staying on the farm during his playing years had its benefits, but the concept of taking a summer break from the game has since faded away. Photo: Supplied

McCutcheon was with the Lethbridge Hurricanes and Medicine Hat Tigers from 2000-02.

When he was 15 he lived on the family farm.

“I was playing bantam hockey and high school hockey … snowmobiling on the weekend. The best time of my life was at 14-15,” said McCutcheon, who was taken by the New Jersey Devils in the 2000 entry draft.

Besides hockey, McCutcheon was passionate about farming and was out on a tractor by the age of 12.

Sutter and Schneider worry that kids lose something when they focus entirely on hockey.

Many players on the Rebels have come through academies, and the programs do churn out quality players. However, Sutter said it isn’t the only way, or the best way, to reach the WHL and the NHL

“It (an academy) does provide a lot of things that minor hockey programs don’t provide… Coaches are paid to work in those academies,” he said.

“There are more opportunities for the kids to play year-round now, but I’m not sure it’s good thing for the player to do so.”

Brent Sutter, former NHL player. Photo: Courtesy Red Deer Rebels

Brent Sutter, former NHL player. Photo: Courtesy Red Deer Rebels

A teenager should have friends outside of hockey, should probably have a part-time job and play a different sport in the summer, he added.

It’s part of the experience of growing up and makes someone a better athlete.

“There are hockey players that can’t even throw a ball because they’re not athletes,” Sutter said.

“Trust me. You can tell the difference when they get to this level – who is the hockey player or an athlete…. I’ve been involved in this industry a long time…. I get both sides of it. All I’m trying to say is that there’s still huge value on an individual that plays different sports.”

When did things change?

Patrick Marleau holds the record for the most games played in the NHL, and his hockey story began on a farm in Aneroid, Sask., near Swift Current.

Marleau was in the WHL in the 1990s, a time when farm kids still returned home to help their parents and likely attended a hockey school for a couple of weeks in the summer.

Patrick Marleau, who holds the NHL record for regular season games played, started his hockey career on a farm near Aneroid, Sask. Photo: San Jose Mercury News

Patrick Marleau, who holds the NHL record for regular season games played, started his hockey career on a farm near Aneroid, Sask. Photo: San Jose Mercury News

The concept of taking a summer break from hockey faded away in the 2000s. After his first season in the WHL, in 2000, McCutcheon was at home in Carman.

He received a pamphlet in the mail from the Hurricanes, which recommended 50 push-ups per day, or a daily jog in the off-season.

“It was pretty low budget.”

A couple of years later, consistent on-ice workouts became normal for junior hockey players in the summer months.

“It flipped,” McCutcheon said.

“If you weren’t doing it, you were behind.”

The intense competition to make the WHL or a earn a U.S. college scholarship has put pressure on parents to spend big dollars on their teenagers.

That could mean $40,000 per year on a hockey academy and summertime camps for a 14-year-old.

Schneider said he has seen many cases where the parents are more invested in hockey than the child. The player might enjoy “wearing the jersey” of a WHL team but really isn’t passionate about the sport.

It might be better if a 16- or 17-year-old hockey player, including kids from farms, had a part-time job and helped pay for the cost of sticks or something, he added.

“I think that’s a great lesson for kids. It weeds out the guys that really want to do it (from) the guys who think they want to do it.”

The odds are long — 97 to 98 per cent of WHL players will not reach the NHL. Despite that reality, every WHL player has an agent, Schneider said.

Sometime in the 2000s, it became clear to McCutcheon that he wasn’t going to make it.

He wasn’t willing to “put his head through the glass” to reach the top tier in the extremely competitive world of hockey.

“The NHL was never Plan 1 in my life.… You don’t realize how hard it is until you’re in it,” he said.

“To get to that next level… you had to be unbelievably good, unbelievably tough or the hardest working player in the world.”

That sentence is what separates the players who make the NHL, whether they grow up in rural Saskatchewan or downtown Toronto.

If a child has the inner drive to skate around pylons for hours, at age eight, that desire is the difference maker.

“I worked with Connor Bedard for two years…. Those guys dig in. They do extra stuff…. They do it because they want to do it,” Schneider said.

As for farm kids, they may have a cultural advantage because leaders in the hockey industry still associate the farm with work ethic and discipline.

“I’m biased … (but) he’ll be a better team player,” Schneider said.

“If you were to ask our current GM and coaching staff, would we be interested in a (hockey player from a farm), every hand would go up.”

Sutter agreed, saying that if a team drafts a farm kid, it knows what it is going to get.

That said, he added, there are fantastic kids in hockey academies across Canada.

However, the old way of doing things, where junior players work on the family farm, play baseball or have a part-time job at McDonald’s in the summer, should be considered, Sutter said.

“I’m not saying one is better than the other, (but) there are some things … (that) were done in the past. Those are still pretty darn good things.”