Editor’s note: The Denver Gazette presents a three-part investigative series on health after hockey for NHL players. Part I examined the life and death of Colorado Avalanche enforcer Chris Simon. Part II digs into the support system for retired players.

Kyle Quincey woke up in the hospital after 6 hours of lost consciousness with 40 stitches across his forehead.

Quincey, a 16-year-old Canadian in the early 2000s, remained in his junior hockey gear.

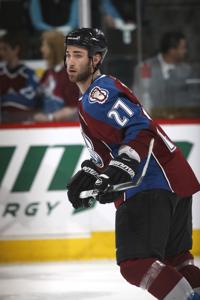

Colorado Avalanche defenseman Kyle Quincey warms up before facing the San Jose Sharks in the first period of Game 3 of the teams’ NHL Western Conference first-round playoff series in Denver on Sunday, April 18, 2010. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski)

David Zalubowski

“It’s pretty traumatic, right?” Quincey recalled. “There were really no rules back then. It was kill or be killed. A very, very dirty hit that kind of started the issues for me. Then I was getting a concussion almost every year since.”

Quincey played 13 NHL seasons, including three with the Avalanche from 2009-12, and experienced unforgettable highs along the way. Playing for a Stanley Cup champion in Detroit. Earning more ice time in Los Angeles. Becoming a No. 1 defenseman for a scrappy Colorado team in 2010 that defied expectations and made it to the playoffs.

But Quincey eventually could not ignore the symptoms — headaches, mood swings, sensitivity to light and sound — resulting from 20 concussions over his life span.

“My first couple were large concussions. Very big hits. Then I got kneed in the head when I played for Colorado. Then they were coming easier. Just little glances from elbows,” Quincey told The Denver Gazette. “You’re getting concussions like every single season, and you’re thinking: ‘That hit shouldn’t have caused that.’”

He retired from professional hockey in 2019 due to head injuries. Quincey couldn’t escape the symptoms. A family emergency made everything worse. In March 2020, his youngest son, Axl, was diagnosed with brain cancer. Quincey entered a mental health crisis.

Struggling NHL players in retirement can face life-threatening consequences without the right support system. Quincey found a light in the darkness.

“What I want people to know is that it’s a combination of all things,” Quincey said. “I was a hockey player since I was 5, and I had a locker room since I was 5. I’m 34 years old and the NHL says, ‘Hey, thank you for your service. Good luck.’ There’s no education on what TBI (traumatic brain injury) means and why I’m having these mood swings, anxiety, depression or suicidal ideations.”

***

John-Michael Liles walked away on his own terms.

The defenseman had contract offers extending his hockey career to 14 NHL seasons when a summer 2017 chat with family put everything into perspective.

“In the end, my wife and I had a 2-year-old daughter,” Liles recalled. “My wife kinda looked at me and said, ‘Hey, when is enough enough? Do we really need to do this?’”

Colorado Avalanche defenseman John-Michael Liles warms up before facing the San Jose Sharks in the first period of Game 4 of the teams’ NHL Western Conference first-round playoff series in Denver on Tuesday, April 20, 2010. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski)

David Zalubowski

Liles was nearly 37 years old. He missed 20 games in his previous season with the Boston Bruins due to a concussion. Liles prioritized health and hung up his skates. Liles returned to his adopted home state of Colorado, where he played eight NHL seasons from 2003-11 for the Avalanche.

Suddenly, the club called upon him again.

“When I first retired, Joe Sakic kind of pulled me aside and said, ‘Hey, you need to help work on growing the alumni,’” Liles told The Denver Gazette. “We really didn’t have a full alumni association 8 years ago. It’s really cool to see the progress that we’ve made.”

Liles is now the longtime Avalanche Association Alumni president and helped it grow from a handful of retired players to now more than 60 former Avs players with local ties in area. Their email newsletter list is global.

Avalanche alumni focus on three pillars:

1. The locker room: Welcoming ex-players to skate at Ball Arena and exhibition games across Colorado to recreate bonds they experienced as NHL teammates.

2. Growing the game: Community outreach exposing Colorado residents to hockey with youth events, coaching clinics and business partnerships.

3. Accessibility: Paying it forward with philanthropy, scholarships, nonprofit partners and a mentorship program.

“There are statistics at the NHL Alumni Association of the challenges within the first three years of retirement,” said Juli Rathke, executive director of the Avalanche Alumni Association. “There is a high prevalence of drugs and alcohol. There is a high prevalence of losing money or mismanagement of funds. There is a high percentage of failed relationships. That three-year window is pretty critical. A lot of the alumni who make it through lend a hand back to guys just coming out of the league.

“It’s a difficult transition.”

***

Gabe Landeskog questioned his identity away from hockey.

The Avalanche captain opened up about his three-year recovery from a significant knee injury in a recent documentary series titled, “A Clean Sheet: Gabe Landeskog.” His emotions were palpable during one specific scene. Landeskog reflected on his mental health challenges from the backseat of a moving vehicle.

“The identity crisis of athletes who have to retire, like that’s for real,” Landeskog said. “As much as I want to tell myself that it’s only what I do, it’s not who I am — am I just lying to myself? Am I just trying to tell myself that to like … try to trick myself? I don’t know. Because I miss every single aspect of it.”

The transition away from professional hockey to normal life also weighs heavily on family members.

Landeskog’s wife, Melissa, spoke on camera about watching Gabe struggle.

“What he’s gone through has pretty much affected every aspect of our relationship. We’ve been challenged in ways that we never thought would be challenged,” Melissa Landeskog said. “After this injury, he was just in such a dark place that I kind of felt like every day he was coming home, and not so much focusing on what he does have, which is his kids who love him to death. I almost feel like he wasn’t Gabe anymore. He wasn’t goofy. He wasn’t playing with the kids.

“He kind of always seemed like he was somewhere else mentally.”

***

Quincey ignored the advice of medical experts.

Your daily report on everything sports in Colorado – covering the Denver Broncos, Denver Nuggets, Colorado Avalanche, and columns from Woody Paige and Paul Klee.

Success! Thank you for subscribing to our newsletter.

He recalled once being examined by the Red Wings.

“I remember in Detroit, the doctor saying: ‘You should probably look at another career or stop playing,’” Quincey told The Denver Gazette. “I’m like, ‘What do you mean? I don’t have an education. I don’t have another option.’ Physically, I was in the prime of my career.”

Quincey understood the potential consequences years later.

In 2015, former NHL defenseman Steve Montador was found dead in his Ontario home. He was 35. His father, Paul, filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the NHL when a postmortem diagnosis confirmed the presence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in his son’s brain. Quincey and a former NHL teammate, defenseman Daniel Carcillo, took notice.

St. Louis Blues’ Ryan Reaves, left, and Colorado Avalanche’s Kyle Quincey get tangled up along the boards during the second period of a preseason NHL hockey game Tuesday, Sept. 21, 2010, in St. Louis. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

Jeff Roberson

“We were both really scared,” Quincey said. “Because we were going down the same path.”

Navigating healthcare can be a challenge for some ex-NHL players.

The league has offered lifetime health insurance coverage since 1992 for retired players who appeared in at least 160 career games, according to the NHL Players’ Association. Participants have up to 120 days after retirement to elect into the plan. A retired player who drops coverage cannot re-enroll in the plan.

The NHL provides full health and dental coverage options with different deductibles/co-pays to lower costs. The top-rated U.S. family plan carries an annual premium around $33,000, the NHLPA said. The least expensive medical plan is under $12,000 per year for family coverage.

“One thing the Avs have been really good at is helping to provide physicals for our guys,” said Liles, a TV analyst covering the Avalanche for Altitude Sports. “A lot of times, there is a financial burden with keeping the NHL insurance. A lot of players aren’t necessarily comfortable with that number on a monthly basis. You’re talking about guys that have dealt with broken bones, concussions, lacerations, and all these different things. … If you’ve gone and played in Europe, you only have (120) days essentially to opt-in to keep your health insurance. That isn’t necessarily a priority if you’re not in the NHL anymore.”

Another potential roadblock is locating medical records.

It can take months, Rathke said, for ex-NHL players to request and receive documents from teams over a long professional hockey career. The Avalanche Alumni Association has considered adding a “healthcare concierge” to assist in coverage options, referrals or finding a new provider.

The path to diagnose and treat brain injuries — specifically CTE — is even more challenging.

“Navigating the healthcare system to get a diagnosis of CTE is incredibly difficult,” said Dr. Meghan Branston from the UCHealth Neurology Clinic in Englewood, with a special clinical interest in sports neurology. “By the time someone receives a CTE diagnosis, the chances are that they’ve seen multiple providers and have gone through the medical system for multiple years. Not having a diagnosis can also be really traumatizing and frustrating. You’re kind of watching your loved one change.

“That’s out of your control and out of their control.”

***

The same question haunted Quincey in his early years of hockey retirement.

Why aren’t you happy?

“It’s the loss of your identity, the loss of your purpose and your mission in life. It’s the loss of your locker room, your accountability network,” said Quincey, vice president of the Avalanche Alumni Association. “Then you’re dealing with actual pain from the shoulder, the knees, the neck, the back, and all of those injuries I had when I left the game. … Then you have your TBI. That’s the hardest one because it’s invisible.”

Quincey discovered hope with assistance from Carcillo, a former NHL teammate, who used ancient methods to address his own traumatic brain injury symptoms.

“He brought me to a ranch, and we did my first large dose of psilocybin in a very therapeutic and intentful way,” Quincey said. “It changed and saved my life.”

Psilocybin is the naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in what are often called “magic mushrooms.” Indigenous cultures across the world have used psilocybin in religious ceremony dating back to the 16th century. In 2022, Colorado voters approved Proposition 122 to decriminalize the use the magic mushrooms.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved psilocybin for use in medical treatments. Oregon is the other state to decriminalize magic mushrooms. But there is growing support in the mental health community for using psilocybin to address traumatic brain injuries.

Former Avalanche defenseman Kyle Quincey founded Do Good Ranch in the Grand Mesa region of Colorado’s Western Slope as a holistic retreat center.

Courtesy of Juli Rathke, Colorado Avalanche Alumni Association

Some psilocybin users report euphoric emotions, deeply personal visions and self-realizations that change their state of being long after the psychedelic effects fade away.

“With what I saw, and it taking away my symptoms of TBI, I got my power back” Quincey said. “I am thriving. I feel amazing. My symptoms are gone, and my brain is firing on all cylinders right now.”

Quincey has since dedicated his life to sharing his wellness path with others.

He spent a year learning from those he called “elders” and ex-Navy Seals with expertise in psychedelics as healing tools. In March 2021, Quincey purchased 280 acres of land in the Grand Mesa region of Colorado’s Western Slope.

Welcome to Do Good Ranch.

Quincey founded the holistic retreat center as a place for veterans, first responders, athletes and anyone seeking mental health solutions absent from pharmaceuticals. The process starts about a month out with a medical intake application, education and planning. A retreat typically lasts about four days.

Guests submit a medical evaluation before a combination of clean eating, outdoor activities, exercise and natural healing. They partake in psilocybin during a sunset ceremony on the final evening.

“The ranch is for anyone that wants to be a better version of themselves,” Quincey said.

It is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Anyone considering psilocybin should first consult a doctor.

But Quincey wants the hockey world to know that a potentially life-saving method exists for anyone struggling with mental health in retirement. The NHL currently lacks a transition program for ex-players. Quincey hopes to fill the gap.

“We dedicated our life to one thing. I mastered the craft of defense. But even from 15 or 16 (years old) when I moved away from home and started being a pro, I didn’t get to master too many other things,” Quincey said. “Now, we’re in the second chapter of our life. This transition program would be a way to learn these modalities and learn these different concepts to really thrive in your second chapter. That’s where you see a lot of guys struggling, because we don’t have the answers.

“We don’t have the tools.”